What We Learned About Allyship from Our Male Staff

What We Learned About Allyship from Our Male Staff

I spoke to our male colleagues about being allies – this is what they said.

As an organisation with a name like Women for Women International, it may be surprising that we count a number of dedicated and compassionate male staff among our global community working towards a more equitable future. Because whilst our mission centres on raising the voices and power of women survivors of war, the change we seek cannot be built by women alone.

Though breaking down patriarchal barriers should not be our burden, the reality is that we need the other half on side. Some of our greatest allies are men – men who work alongside us, who challenge patriarchal norms from within and who model a different kind of masculinity.

I spoke to several of our male colleagues – from Iraq and South Sudan, to DRC and the UK. I asked what allyship means to them, how their work has shaped their understanding of gender justice and what they’ve learned from the women in their lives. What emerged was not just a collection of stories, but a testament to the quiet, determined work of transformation – both personal and societal.

Many of the men who work at Women for Women International have a long-standing commitment to challenging inequality. For Aram, our Country Director in Iraq, joining the organisation felt like a natural extension of the work he was already doing: “I had long been working to address inequalities towards women in a male-dominant and patriarchal context. Joining the organisation was a golden opportunity to serve that mission more directly.”

Moses, a Programme Manager in South Sudan, shared how growing up as the child of a soldier shaped his worldview:

I was raised by my mother alone while my father served in the war. I understand the impact that conflict has on women and girls. That’s why I joined – to give back to the women in our communities.

For our colleagues, allyship is not performative – it's practical, principled and often uncomfortable. Working in a women’s rights organisation as a man often invites questions, skepticism and even ridicule, and many shared anecdotes reflecting society’s prejudiced and narrow beliefs about men’s participation in the pursuit of gender equality. Joseph, an Economic Empowerment Officer in South Sudan, shared:

Some men ask me, ‘What are you doing in a women’s organisation? Are you a woman?’ Others say, ‘You are spoiling our women; now they don’t respect us.’

Another male staff member admitted that “People often ask how, as a man, I can work with an NGO that has ‘women’ in its name twice. To be honest, I’ve experienced a bit of bullying around this.”

Similarly, Laurence, our Head of Marketing and Communications in the UK, shared that “there’s the odd creased brow and question of ‘But you’re a man?’” when he tells other men about his line of work.

Most negativity, he says, tends to focus around the argument that men suffer too, while others suggest that this work is somehow an overreach of ‘PC culture’. “That tends to lead to some, shall we say, interesting conversations.”

Challenging norms around traditional masculinity is not easy, and doing so as a man presents its own set of difficulties – often leaving men in a position where their own masculinity is questioned. Because despite growing awareness, male allyship is still widely misunderstood.

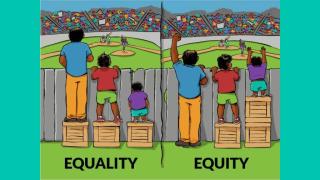

Many men, our staff noted, see gender equality as a zero-sum game – believing that empowering women means disempowering men. “Some think that when women are equal to men, it will create power struggles,” said one team member.

Meanwhile, Aram shared that in his context in Iraq, “male allyship is seen as a ‘western value’ that only ‘weak’ men openly promote”.

In the UK, Laurence said that “people often say that they support equality, but when you talk about the need for equity first – which is about correcting existing imbalances – that’s when it feels like an attack.”

For all our male staff, working at a women’s rights organisation has challenged and evolved their own understanding of what it means to be an ally. For one colleague, it means “listening, understanding and amplifying women’s voices without overshadowing them.” Another rooted allyship in personal accountability:

It’s about correcting ingrained patriarchal behaviors – first in myself, then in others. I would never claim to be the perfect ally, but I’m conscious of my role and try to hold myself to a better standard.

This awareness – that allyship is not a destination, but a daily commitment – was echoed throughout their reflections, along with the understanding that toxic masculinity is not only harmful to women.

In South Sudan, Joseph described how men are conditioned to suppress emotion and adopt dominance as a marker of manhood. “Most men won’t show vulnerability for fear of being called weak. This leads to depression, aggression and stress.”

In the UK, Laurence reflected on the mental health crisis among men, often linked to this same culture of silence:

There’s this belief that men shouldn’t express emotion or ask for help. It isolates people and damages relationships. I’ve seen it firsthand – and if I’m honest, I struggle with it myself.

James, our Director of Safeguarding and Security, offered an interesting reframe: “It’s probably an unpopular thing to say, but I identify as an ‘alpha male’. But for me, that aspect of my character has never meant that I seek dominance."

"True strength lies in protecting and supporting whoever needs it, so to me the whole idea of toxic masculinity is actually a massive display of weakness and insecurity. I often make a point of deferring to female colleagues in patriarchal contexts to challenge norms. That doesn’t make me less of a man – it affirms who I am.”

But are these more progressive attitudes a response to working in a women’s rights organisation, or does such a workplace attract people who already hold these beliefs? It seems to be a combination of both, and our male staff often credit the women in their lives for shaping their understanding of gender justice.

Pacifique, a Social Empowerment Officer in the DRC, grew up in a family of 12. His mother, he recalled, made no distinction between boys and girls when it came to chores or discipline. “We were all treated the same – and that has shaped how we are raising our own children today.”

Gotau, an Economic Empowerment Trainer in Nigeria, thanked his mother and elder sister for teaching him “resilience, determination and commitment to raising an impactful generation after them.”

Like Pacifique and Gotau, most of the more than thirty male staff we surveyed mentioned their mothers when asked about a woman in their life that inspires them. This validates a core premise of our work – that women are powerful influences within their families and communities, and investing in their potential leads to a ripple effect of positive change for generations to come.

Working in a women’s rights organisation often deepens – not just affirms – men's commitments to building a more equal world. Laurence, for example, acknowledged that he hadn’t fully understood the scale of conflict-related sexual violence until he joined Women for Women International. “Reading the stories of the women we serve, seeing their journeys... it gives me incredible respect for their courage and power.”

James, after decades in the security and humanitarian sector, shared simply:

Any preconceptions I had about the lives women lead and the challenges they face have long been stripped away.

Parallel to their personal journeys of learning and growth, many of the men on our country teams are leading efforts to engage other men directly through our Men’s Engagement Programme (MEP) - a cornerstone of our approach to building more peaceful, equitable communities.

In the DRC and South Sudan, staff have seen dramatic shifts in attitudes and behaviors. “Men begin to challenge traditional norms,” Joseph shared, “develop empathy, and adopt healthier, non-violent ways of relating to their families. Some even disseminate the skills they’ve learned to men who didn’t attend the programme.”

Still, the change is not always immediate. As Aram cautioned, “Some negative attitudes are deeply rooted, and it takes time for the increased awareness and knowledge to translate into actual behavior.” But even small shifts – men gradually beginning to reflect on and question harmful norms that they have always passively accepted – can ripple outward into powerful societal changes.

When we circulated the survey on which this blog is based, it took several rounds of encouragement before enough of our male colleagues filled it out. Focused on the work itself, they either didn’t have the time to answer a survey about it or the desire to attract attention to their personal role within it.

There is much to learn from this modest determination. Real change happens not through grand gestures, but through sustained, often quiet efforts to shift power, open space and share responsibility. We are grateful to our male staff not only for their commitment to being allies, but to raising the standard for what allyship means.

Read more

Every woman has the power to transform her own life — and the lives of girls around her. On International Day of the Girl Child, we are spotlighting the barriers to equality facing girls in Nigeria and the women working to clear the way.

Since the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan in August 2021, Afghan women have experienced profound changes in their daily lives. The de facto government has reinstated many restrictions, severely limiting the rights and freedoms of women and girls.

Yet, in the face of these challenges, Afghan women have shown extraordinary determination and strength, finding ways to resist and adapt. Here, we explore five significant ways their lives have changed, highlighting both the difficulties they face and their ongoing fight for their rights.

Amina

subtitle:

In Afghanistan, Amina* dares to stand up for women’s rights. Women have been virtually erased from public life over the past two years: banned from parks, gyms, restaurants, most jobs and education. Opposing these restrictions is incredibly dangerous, but Amina dares to keep teaching in our training centre. She braves the constant scrutiny of government authorities and she dares to spread the word that education should be the right of every woman and girl.

*Although the story is real, for reasons of security and privacy, we're not using Amina's real name or photograph.