Why is a Climate Justice Lens Important?

Why is a climate justice lens important?

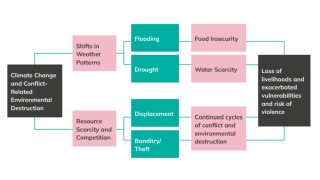

Climate justice and the intersection of environment, women and conflict

Last month, I had the pleasure and privilege of attending the Third Environmental Peacebuilding Conference to speak on a panel entitled “Investing in Women as Agents of Environmental Peacebuilding”. During the panel, I was asked why Women for Women International uses a climate ‘justice’ lens to approach our programming and advocacy to strengthen women’s resilience at the intersection of conflict and climate shocks.

Why, indeed?

At the risk of stating the obvious: Women for Women International did not invent the climate justice lens or movement. For those of you who may be new to the terminology, climate justice can be summarised as a framework and movement that recognises that those communities that have contributed the least to cause the global climate crisis are feeling the greatest impact. And if you were to further disaggregate within those communities, we would say it’s women who are most impacted. And despite this disproportionate impact, it’s also women who are least consulted on how the climate crisis is affecting their communities. It won’t be a surprise therefore that it’s also women who are least included when it comes to decisions about what the solutions to issues within their own communities look like. This is why we need a climate justice lens.

‘Justice’ may evoke thoughts of a courtroom or crime and punishment rather than thoughts of climate. But Women for Women International believes that there IS a place for justice in the conversation around climate and security, because ‘justice’ is necessary to describe both what we need to do and how we need to do it.

WHAT do we need to do about climate injustice

In our research, Women for Women International surveyed about 1,000 women in communities where we work or where we support women-led organisations to respond to conflict. These women’s daily lives are: affected by conflict; they live under the poverty line; with limited literacy and education; and they may be socially-marginalised in some way due to their intersecting social identities or experience of gender-based violence.

From the beginning of our research, we already knew that the language that women in our programmes use to talk about climate and environment is different than the language used in policymaking spaces. Women in Afghanistan, the DRC, Iraq, Nigeria, Rwanda, and South Sudan primarily talk about the direct and indirect effects of climate and environmental stressors in relation to the unique effects those stressors or shocks have on their lives and their resilience – particularly economic livelihoods and health. In addition to climate and environment shocks eroding their resilience, women also talked about how conflict further weakened or destroyed any supportive infrastructure – like health centres, water wells, etc. - that could help them cope with these impacts.

To these women, who are most affected by the challenges we are all working on, you cannot have separate conversations about climate mitigation and climate adaptation. These conversations are inseparable and so too are the solutions which women in conflict-settings say must address urgent adaptation to these challenges, in addition to mitigation or environmental protection. These solutions require policymakers, funders and organisations like Women for Women International to break down silos in our work and collaborate extensively so that environmental programming includes a conflict and gender lens, and that conflict prevention or resolution work includes an environmental lens. According to a climate justice framework, these solutions also require women affected by these challenges to be actively engaged in the design and implementation of relevant policy and programmes to address them.

HOW do we address the issue

As mentioned, the burden and moral responsibility to fund the solution to these challenges should be borne by countries that contributed the most to the global crisis, but to be effective, and to be ‘just’, the solutions themselves need to be built by the people most affected, and this ties back to the topic of the panel I spoke on: investing in women peacebuilders.

As part of our research, we interviewed women peacebuilders and women-led organisations that work on women’s resilience and climate in these contexts to understand their experiences and recommendations. And what we heard is that there is a long way to go towards equity – much less justice - in partnerships and implementation of solutions.

Women themselves identified the gaps in their own technical capacity to speak the language necessary to engage in these spaces, but also expressed that they knew the importance of being able to do so because of the high stakes involved. They called for greater education and training opportunities for them and their organisations to learn about opportunities and priorities, and to connect with other women-led movements and organisations operating at the intersection of conflict and climate shock.

This is exactly the kind of work our Conflict Response Fund (CRF) partners in Burkina Faso told us about. They emphasised the potential of cross-learning and sharing using their example of learning from women in Mali. Women in Mali have been adapting their response to the climate crisis by harvesting and processing soybeans to produce products like milk and cake. By exchanging lessons on climate adaptation, especially between conflict contexts affected by the same climate trends, partners in Burkina Faso and Mali were able to collectively contribute to each other’s solutions to responding to the climate crisis and building their agricultural productivity.

Women also overwhelmingly called for their inclusion in relevant decision-making – such as at negotiation tables for peace, natural resource management and socioeconomic policies. Women do not want to be relegated only to project implementation, but rather they also want to lead preventative efforts via natural resource management that currently seems to happen unilaterally between governments and corporations.

WROs describe how oil companies take advantage of conflict-affected countries’ weak governance and infrastructure to deposit petroleum and waste in communities and water sources. Oil companies do this without accountability for impact on communities and without initial input from civil society on negotiations that permit corporate activity in their communities in the first place.

Women also want additional funding to do the necessary work at the intersection of conflict and gender and environment. This may seem intuitive, but women that we interviewed for our research indicated that it is still common for donors to ask them to ‘green’ their work without offering additional funding to do so, for example:

- WROs noted that interest in climate sensitive programming has gone up even as development budgets are reduced in response to the diversion of funds to address active conflict and humanitarian crises, such as the war in Ukraine.

- In Syria, WROs shared examples of donors asking about the commitment of the WROs to using clean fuel to implement their programmes in an out of touch attempt to integrate climate impacts into their funded projects. WROs described their shock at being asked to seek out ‘clean’ fuel at a time when certain parts of Syria are under active siege and are lucky to have any access to fuel.

So, Women for Women International believes that ‘climate justice’ helps us reach a practical framework that appropriately addresses both the burden and responsibility for environmental damage and climate change. Climate justice also prioritises support and solutions to address challenges facing most affected populations right now and demands that those most affected – especially women - are adequately supported to lead and design those solutions themselves through education, inclusion, and funding.

Read the report

“Cultivating a more enabling environment: Strengthening women’s resilience in climate-vulnerable and conflict-affected communities”

To read more about our research and policy recommendations on strengthening women’s resilience at the intersection of climate change and conflict, check out our recent report here.

This report elevates the perspectives and experiences of women survivors of war and conflict, highlighting the effects of extreme weather, environmental degradation, poverty, violence and conflict on their lives.

Keep reading

As political figures and activists engaged in discourse, addressing the effects of climate change through political leadership, a small group of women in South Sudan assembled less than 1000 miles away. Faced with a withering supply of crops and livestock, they’re pursuing an avenue of farming that will make them more resilient.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, restrictive gender norms make it difficult for women to purchase land in their own name. Read Gorette, Furaha and Gentille's stories - three of our programme graduates who have defied the odds and now help other women to do the same.

July 3rd is International Cooperatives Day, and we're celebrating the power of women's collective enterprises to transform lives and communities.